Summer 2022

"He who would search for pearls must dive below..." *

Detail from Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres portrait of Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn, Princesse de Broglie, c. 1851–1853.

The Book of The Pearl, written by George Frederick Kunz and Charles Hugh Stevenson and published in 1908, is still one of the best references for all things pearl related.

"The pearl touches us with the same sense of simplicity and sweetness as the mountain daisy or the wild rose. It is absolutely a gift of nature, on which man cannot improve. We turn from the brilliant, dazzling ornament of diamonds or emeralds to a necklace of pearls with a sense of relief, and the eye rests upon it with quiet, satisfied repose and is delighted with its modest splendor, its soft gleam, borrowed from its home in the depths of the sea."

George Frederick Kunz and Charles Hugh Stevenson

Ancient literature abounds with references to pearls, like the story of Cleopatra's banquet. Legend has it Cleopatra placed a bet with Marc Antony that she could serve the most expensive dinner in history. She wore a pair of magnificent (and pricey) pearl earrings, but served simple dishes. As the meal came to an end, Cleopatra removed one of her earrings, dropped it in a glass of wine (maybe vinegar) and drank it, winning the bet. The story is depicted in many paintings in the world of Western art, one of the most well known being "The Banquet of Cleopatra" by Italian artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, c. 1744. There are versions in Dutch Golden Age painting and Flemish Baroque painting, as well as 17th and 18th century "portrait historié," or "historicized portraits," which show wealthy women posing as Cleopatra—like this one by François Lemoyne, c. 1725.

Girl with a _____ Earring . . . One of the most famous pearls in art history is undoubtedly the one featured in Dutch Golden Age painter Johannes Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665. The gem appears to be about the same size as La Peregrina (more on that later) but is it even really a pearl? In 2014, Dutch astrophysicist Vincent Icke raised doubts about the material of the earring. Based on its large size, pear-shape, and reflectiveness, Icke deduced that it looks more like polished tin than pearl. It's also been argued that Vermeer would not have been able to afford or gain access to a pearl as big as the one pictured, so it could potentially be a faux piece made of varnished glass, or perhaps it never actually existed in reality at all . . .

A drop fell on the apple tree / Another on the roof; / A half a dozen kissed the eaves, / And made the gables laugh. / A few went out to help the brook, / That went to help the sea. / Myself conjectured, Were they pearls, / What necklaces could be! / The dust replaced in hoisted roa / The birds jocoser sung; / The sunshine threw his hat away, / The orchards spangles hung. / The breezes brought dejected / And bathed them in the glee; / The East put out a single flag, / And signed the fete away.

Emily Dickinson

It's easy to get swept up in the splendor of pearls without thinking about where they've come from and how they've gotten here . . . "The lady who cherishes and adorns herself with a necklace of Ceylon pearls would be horrified were she to see and especially to smell the putrid mass from which her lustrous gems are evolved," write Stevenson and Kunz in The Book of the Pearl. Like gold and diamonds, the journey of the pearl has historically involved the exploitation of people and the planet. Before advancing technology altered the industry, and long before the invention of the cultured pearl (more on that below), people braved treacherous conditions—both underwater and on land—in exchange for meager wages. Pictured here, a romantic vision of pearl diving by Italian Renaissance painter Alessandro Allori, with vessels full of pearls and strands woven through up-dos.

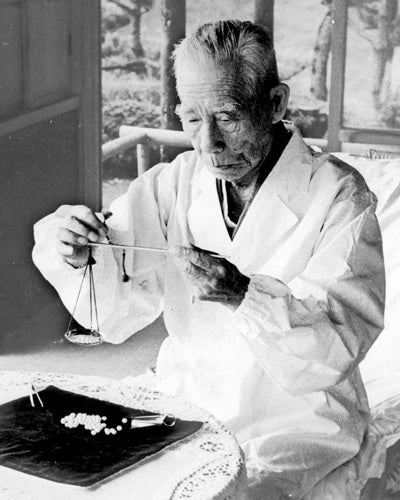

Kokichi Mikimoto, the "Pearl King," is the name most closely associated with the development of cultured pearls. Mikimoto was born in Japan's Shima Province in 1858, the eldest son of an udon shop owner. When his father died, Mikimoto, not yet a teenager, took on the responsibility of supporting his family. Watching pearl divers unload their finds at the shore as a child had launched his fascination with pearls. After years of investigation and experimentation, Mikimoto successfully created a culturing process. (Though two men, Tatsuhei Mise and Tokichi Nishikawa, were close behind—and Mikimoto later adopted the Mise/Nishikawa method in his own operations.) A savvy businessman, Mikimoto sent exhibitions of his pearl jewelry to museums across the planet, campaigning for international acceptance of the cultured pearl, stating “My dream is to adorn the necks of all women around the world with pearls.”

Nature becomes the ultimate designer each time a pearl is born. I can hold a single flawless pearl in my hand and know there are centuries of wisdom hidden within it.

Sumiko Mikimoto

There’s a reason why the pearl has been an object of fascination and attraction since it was first discovered all those years ago. Why it appears again and again in artworks, in collections of crown jewels, on red carpets, on the necks and ears of the world’s most stylish men and women. Why it is always included on lists of must-have items—like the Gemological Institute of America’s 2014 article ‘11 Pieces of Jewelry Every Woman Should Own,’ which inspired Liesbet Bussche's series of posters ‘Blueprint of an Entire Jewellery Collection in 11 Pieces,’ (a commentary on the absurdity of such lists) with a strand of pearls clocking in at number five (pictured here). Part of the pearl's power is its timelessness, its must-have-ness, its everywhere-ness. And at the same time, its complex simplicity, its gentle drama, its quiet beauty. Pearls are so many things, for so many different people, all at once. And wearing them feels like wearing a piece of something greater. That is the magic of pearls.