"He who would search for pearls must dive below..." *

There is so much to say about pearls. Pearls as symbols of purity, and pearls as symbols of power. Pearls pinned to our grandmothers’ sweaters and placed in our mothers’ jewelry boxes. And now, pearls on the most popular pop stars (Harry Styles, Justin Bieber, Dua Lipa) and pearls trending on Tiktok (Vivienne Westwood’s three-strand choker) . . .

There’s the story of Cleopatra dissolving a pearl earring in a glass of wine, and the story of Kokichi Mikimoto, the Japanese entrepreneur who is credited with launching the cultured-pearl industry.

Once the most expensive jewelry in the world, pearls decorate paintings of royals in portrait galleries, and Hollywood royals on red carpets. (Not to mention politicians.)

If diamonds are forever, then pearls are certainly permanent too.

* John Dryden, The Wild Gallant, 1669.

"The pearl touches us with the same sense of simplicity and sweetness as the mountain daisy or the wild rose. It is absolutely a gift of nature, on which man cannot improve. We turn from the brilliant, dazzling ornament of diamonds or emeralds to a necklace of pearls with a sense of relief, and the eye rests upon it with quiet, satisfied repose and is delighted with its modest splendor, its soft gleam, borrowed from its home in the depths of the sea."

George Frederick Kunz and Charles Hugh Stevenson

Ancient literature abounds with references to pearls, like the story of Cleopatra's banquet . . . Legend has it Cleopatra placed a bet with Marc Antony that she could serve the most expensive dinner in history. She wore a pair of magnificent (and pricey) pearl earrings, but served simple dishes. As the meal came to an end, Cleopatra removed one of her earrings, dropped it in a glass of wine (maybe vinegar) and drank it, winning the bet. The story is depicted in many paintings in the world of Western art, one of the most well known being "The Banquet of Cleopatra" by Italian artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, c. 1744. There are versions in Dutch Golden Age painting and Flemish Baroque painting, as well as 17th and 18th century "portrait historié," or "historicized portraits," which show wealthy women posing as Cleopatra—like this one by François Lemoyne, c. 1725.

Girl with a _____ Earring . . . One of the most famous pearls in art history is undoubtedly the one featured in Dutch Golden Age painter Johannes Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665. The gem appears to be about the same size as La Peregrina (more on that later) but is it even really a pearl? In 2014, Dutch astrophysicist Vincent Icke raised doubts about the material of the earring. Based on its large size, pear-shape, and reflectiveness, Icke deduced that it looks more like polished tin than pearl. It's also been argued that Vermeer would not have been able to afford or gain access to a pearl as big as the one pictured, so it could potentially be a faux piece made of varnished glass, or perhaps it never actually existed in reality at all . . .

-

Diana, Princess of Wales, and her pearl choker, which combined seven strands of pearls with a sapphire and diamond brooch given to her by Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. Diana wore the necklace often, most famously when she danced with John Travolta at the White House in 1985, and in 1994 with the iconic “revenge dress” at a fund-raising dinner in London, on the same day that Prince Charles went public about his affair with Camilla Parker Bowles.

-

Arguably one of the most well–known pearl–wearers—Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly in 'Breakfast at Tiffany's.' The five-strand necklace from this scene was designed by Roger Scemama, a French jewelry designer who frequently collaborated with haute-couture design houses like Givenchy, Dior, Lanvin, and Yves Saint Laurent.

-

“Lace is one of the most wonderful imitations of nature. But pearls are perfect for every occasion.” — Coco Chanel and her pearls, photographed by Man Ray in 1935.

A drop fell on the apple tree / Another on the roof; / A half a dozen kissed the eaves, / And made the gables laugh. / A few went out to help the brook, / That went to help the sea. / Myself conjectured, Were they pearls, / What necklaces could be! / The dust replaced in hoisted roa / The birds jocoser sung; / The sunshine threw his hat away, / The orchards spangles hung. / The breezes brought dejected / And bathed them in the glee; / The East put out a single flag, / And signed the fete away.

Emily Dickinson

It's easy to get swept up in the splendor of pearls without thinking about where they've come from and how they've gotten here . . . "The lady who cherishes and adorns herself with a necklace of Ceylon pearls would be horrified were she to see and especially to smell the putrid mass from which her lustrous gems are evolved," write Stevenson and Kunz in The Book of the Pearl. Like gold and diamonds, the journey of the pearl has historically involved the exploitation of people and the planet. Before advancing technology altered the industry, and long before the invention of the cultured pearl (more on that below), people braved treacherous conditions—both underwater and on land—in exchange for meager wages. Pictured here, a romantic vision of pearl diving by Italian Renaissance painter Alessandro Allori, with vessels full of pearls and strands woven through up-dos.

Kokichi Mikimoto, the "Pearl King," is the name most closely associated with the development of cultured pearls. Mikimoto was born in Japan's Shima Province in 1858, the eldest son of an udon shop owner. When his father died, Mikimoto, not yet a teenager, took on the responsibility of supporting his family. Watching pearl divers unload their finds at the shore as a child had launched his fascination with pearls. After years of investigation and experimentation, Mikimoto successfully created a culturing process. (Though two men, Tatsuhei Mise and Tokichi Nishikawa, were close behind—and Mikimoto later adopted the Mise/Nishikawa method in his own operations.) A savvy businessman, Mikimoto sent exhibitions of his pearl jewelry to museums across the planet, campaigning for international acceptance of the cultured pearl, stating “My dream is to adorn the necks of all women around the world with pearls.”

Ama — Women of the Sea

Long-famed as skilled divers, Japan’s ama could descend as deep as sixty feet in water that was often rough, freezing, and infested with dangerous creatures—without any gear! While traditionally foraging for seaweed, abalone, and other sea foods, the ama found work as pearl divers when the Japanese pearl industry began to grow. They dived wearing only loincloths, goggles, and headscarves adorned with symbols meant to ward off evil and bring luck. The term ‘Ama’ dates back to as early as 750 AD, and though the tradition is still maintained, much of ama culture is becoming lost with time—but there are still ama at work today!

Above, ama photographed by Italian photographer Fosco Maraini in the early 1960s, featured in his book The Island of the Fisher-women.

-

Elizabeth Taylor wearing La Peregrina for her cameo in the 1969 film Anne of the Thousand Days.

-

Elizabeth of Bourbon painted by Peter Paul Rubens.

-

Margaret of Austria, Queen of Spain painted by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (c. 1606).

La Peregrina

“I just casually opened the puppy’s mouth, and inside his mouth was the most perfect pearl in the world.”

The perfect pearl Elizabeth Taylor is referring to is La Peregrina—which was originally discovered off the coast of Panama in the mid 16th century (not in a puppy’s mouth—Taylor had lost it in her suite at Caesar’s Palace).

The pearl was a Valentine’s gift from Richard Burton, purchased for $37,000 from Sotheby’s London in 1969. But before it found its place around the movie star’s neck, La Peregrina, which translates to “The Pilgrim” or “The Wanderer,” was passed around Europe’s royals for centuries.

Upon its discovery, King Phillip II of Spain presented the pearl as a bridal gift to Queen Mary I of England. After her death in 1558, the pearl was returned to the Kingdom of Spain, where it remained in the collection of crown jewels for some 250 years.

In the 1800s, the pearl ended up in the hands of Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte, who briefly ruled Spain. He later willed the pearl to his nephew, who would become Napoleon III, Emperor of France. While exiled in England, the emperor sold the pearl to the Duke of Abercorn as a gift for his wife, the Duchess Louisa Hamilton. Rumor has it that the pearl was misplaced at both Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace—before Taylor’s Caesar’s Palace scare!

La Peregrina appears in numerous royal portraits—Elizabeth of Bourbon painted by Peter Paul Rubens and Margaret of Austria, Queen of Spain painted by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (c. 1606) are just two examples. And on the silver screen—pictured above, Taylor wears La Peregrina for her cameo in the 1969 film Anne of the Thousand Days.

Later on, Taylor worked with Al Durante of Cartier to redesign the necklace, creating a choker of rubies, diamonds, and pearls, with La Peregrina as the focal point. Taylor treasured the necklace until her death in 2011, when it was sold to an anonymous buyer in a Christie’s New York auction for over $11 million.

Where will this wandering pearl turn up next?

And speaking of Cartier…

You may recognize the Cartier Mansion, but did you know that it was paid for in pearls?

Built in 1905, the mansion at 653 Fifth Avenue was originally owned by a businessman named Morton F. Plant. By 1916, the neighborhood (once home to some of America’s most prominent families, like the Vanderbilts and Astors) had shifted—businesses had moved in, and nearly all of Plant’s wealthy neighbors had moved out (i.e. further up Fifth Avenue). Plant’s wife, Mae Caldwell Manwaring Plant, had become obsessed with a two-strand pearl necklace—believed, at the time, to be the most expensive necklace in the world—recently released by Cartier (who had set up shop a few blocks away at 712 Fifth Avenue).

So, in 1917, the Plants and the Cartiers struck a deal—the necklace in exchange for the mansion. 653 Fifth Avenue has been the New York home of Cartier ever since—and it is one of the last remnants of a long-gone world that used to exist in this stretch of the city.

-

A 1626 portrait by Dutch painter Jansz van Miereveld portrays George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham, draped in pearls.

-

Maharaja Pratap Singh Gaekwar of Baroda wearing the Baroda pearls for the celebration of his fortieth birthday in 1948, photographed by Henri Cartier-Bresson. The famous seven-strand pearl necklace, which had been created in the mid-19th century for one of the Maharaja's predecessors, a noted jewelry collector, gained international recognition in 1908 when it was featured in the Book of the Pearl. The Baroda pearls have a storied history, and in 2007, a two–strand necklace made of selected pearls from the original piece suddenly appeared at a Christie's auction in New York, setting a record price of $7.1 million, the highest ever paid for a pearl necklace at auction.

-

Harry Styles at the 2019 Met Gala, wearing head-to-toe Gucci and a pearl earring in his right earlobe. (He was rumoured to have pierced his ear specially for the occasion).

Men in Pearls

“The history of men in pearl necklaces,” writes Nick Haramis in a New York Times article Pearls Are a Boys Best Friend, “can be traced to the early 16th century, during the Mughal Empire in India, when long strands could be seen on the emperor Babur and his male descendants. In Europe, Henry VIII wore clothes embroidered with them during his reign as the king of England in the first half of the 1500s…Pearls—hard yet smooth, timeless yet trendy, iconic yet rare—offer an introduction to style that allows the wearer to have it both ways. They are a contradiction and a coalescence, a gateway to genderless fashion that emphasizes the very distinction it’s meant to dismantle. Pearls are elevated objects from the bottom of the sea, and they represent exactly what they are: a silky orb that lives inside an armor of rock-hard grit.”

Above, a 1626 portrait of George Villiers, the first Duke of Buckingham, draped in pearls, by Dutch painter Jansz van Miereveld. Sita Devi, Maharani of Baroda, fastening the Baroda pearls around the neck of her husband, Maharaja Pratap Singh Gaekwar of Baroda. And Harry Styles (who often rocks pearl necklaces) at the 2019 Met Gala, wearing a pearl earring in his right earlobe.

Just like in portraits, pearls have adorned still lifes throughout history. In Cabinets of Curiosities, a 17th century trompe l'oeil painting by German artist Johann Georg Hainz, strands hang from hooks and peek out from a box, and larger pearl drops dangle from earrings and cameos. Secular still lifes like this one were meant to demonstrate the wealth of the patrons who commissioned them—in this case, the King of Denmark—displaying an abundance of various treasures to impress viewers.

Nature becomes the ultimate designer each time a pearl is born. I can hold a single flawless pearl in my hand and know there are centuries of wisdom hidden within it.

Sumiko Mikimoto

-

Maija Vitola

"Birth" Brooch. Hand carved camel bone, silver, pearl.

-

Reka Lorincz

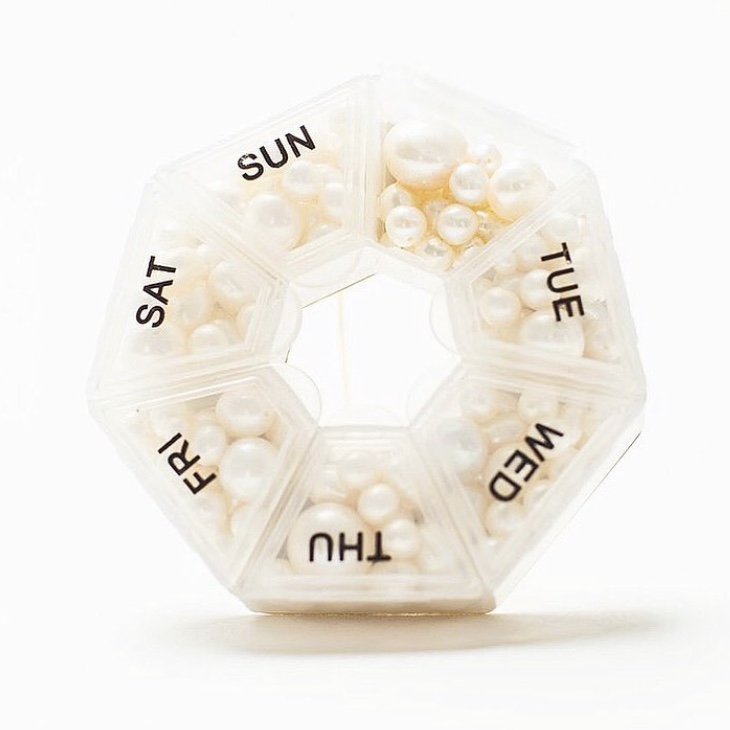

'Monday to Sunday' Brooch, 2017. Pearls, gold-plated brass, plastic pill box.

-

Kim Buck

'String of Pearls with Gold Lock' 2003. Collection of MAD, New York.

Above, a small selection of some favorite contemporary pearl pieces — by Maija Vitola, Reka Lorincz, and Kim Buck.

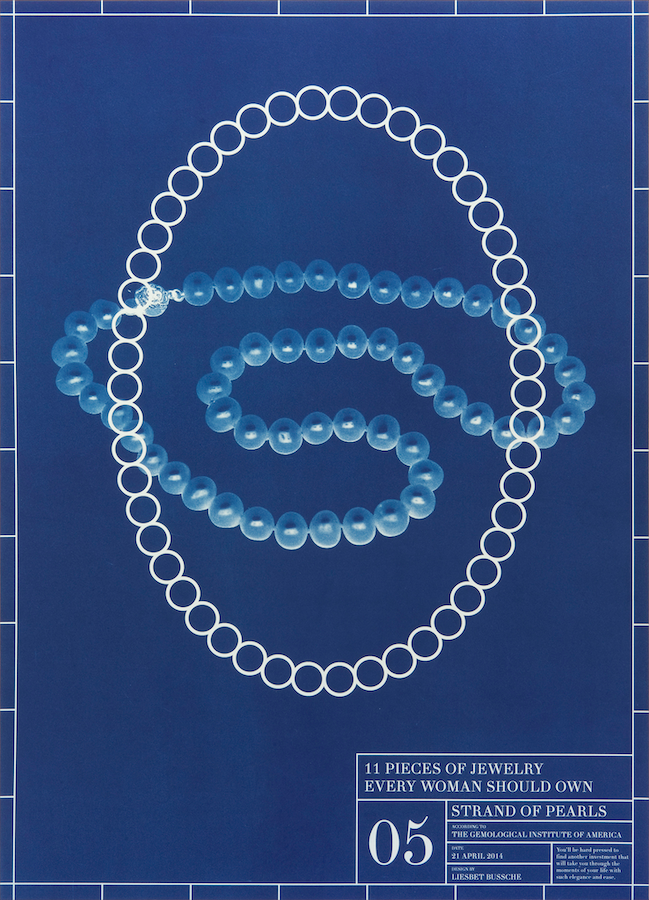

There’s a reason why the pearl has been an object of fascination and attraction since it was first discovered all those years ago. Why it appears again and again in artworks, in collections of crown jewels, on red carpets, on the necks and ears of the world’s most stylish men and women. Why it is always included on lists of must-have items—like the Gemological Institute of America’s 2014 article ‘11 Pieces of Jewelry Every Woman Should Own,’ which inspired Liesbet Bussche's series of posters ‘Blueprint of an Entire Jewellery Collection in 11 Pieces,’ (a commentary on the absurdity of such lists) with a strand of pearls clocking in at number five (pictured here). Part of the pearl's power is its timelessness, its must-have-ness, its everywhere-ness. And at the same time, its complex simplicity, its gentle drama, its quiet beauty. Pearls are so many things, for so many different people, all at once. And wearing them feels like wearing a piece of something greater. That is the magic of pearls.